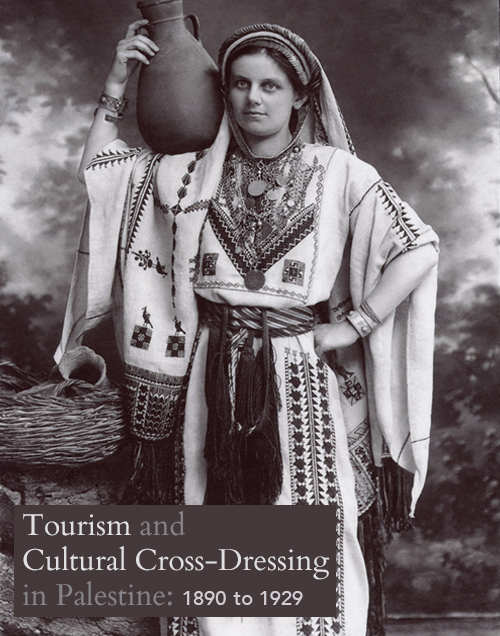

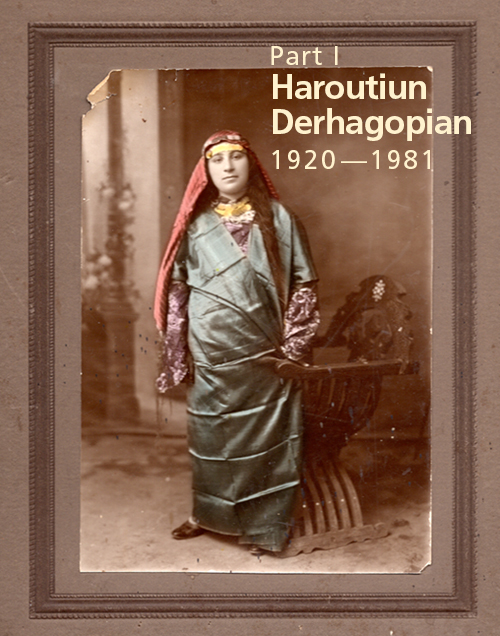

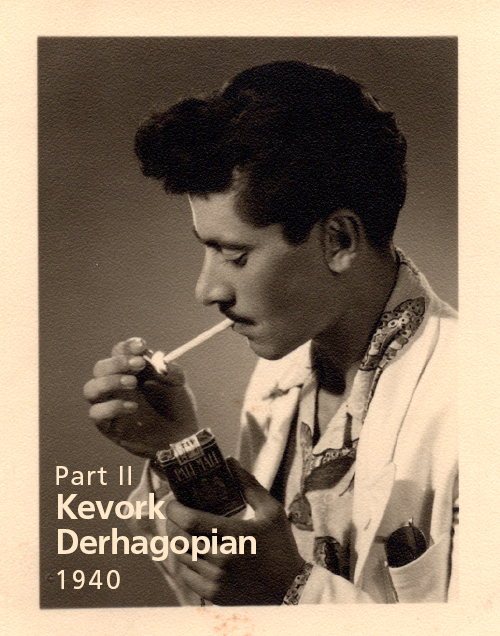

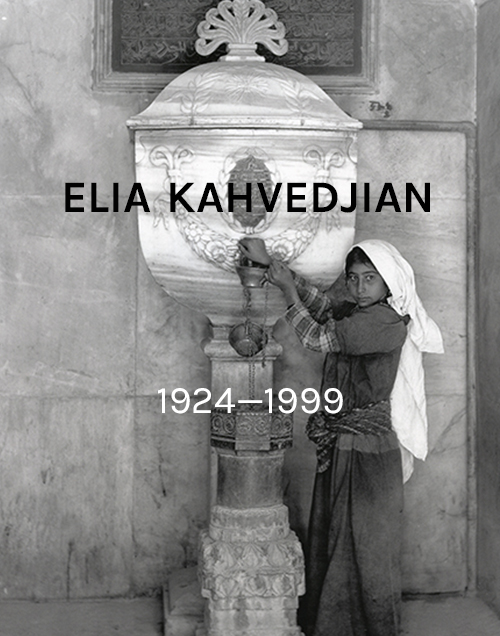

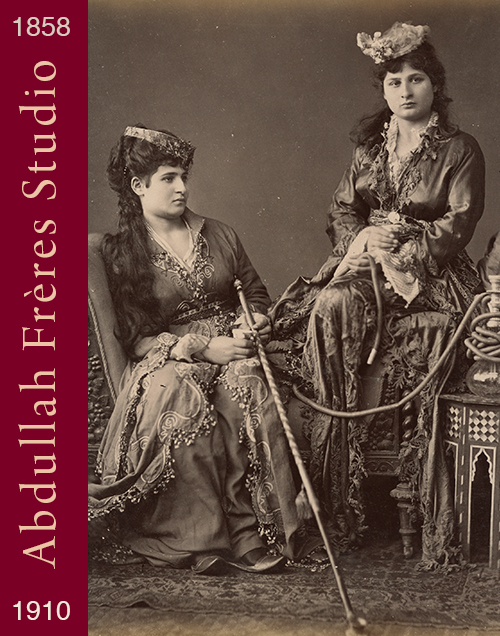

Several years ago while researching material for my book The Armenians in the Ottoman Empire: An Anthology and a Photo Essay, I had the opportunity to study the Pierre de Gigord Ottoman Collection and the Jacobson Middle East Collection at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, California. As I delved into thousands of images within these two extraordinary collections, I made a personal discovery. Armenian photographers commanded a significant role in the development of photography in the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. Thus, they were undoubtedly pioneers who played a dominant role in the early history of Near East photography.

There were many reasons for why the Armenians became involved in Near Eastern photography during the formative years. As noted by Badr El-Hage, some of these reasons were political and economic, and others related to increasing cultural and scientific activity in the community. Armenians were the second largest minority group in Constantinople, and as a minority group they were generally engaged in commercial and industrial activity. With photography as a fairly new invention or craft, it fell into the hands of the minority citizens who were often the artisans. Armenians were also keen to adopt western trends, ideology and innovative technology such as photography which was attributed to the influence and the teachings by the Protestant and Catholic missionaries. Furthermore, Armenians frequently worked as pharmacists and chemists in many parts of the empire which gave them the knowledge to use newly invented photographic processes such as the daguerreotype which required an understanding of chemistry.

During the early history of photography in the Ottoman Empire, the imperial court run by the Sultans embraced the practice of this medium and used photography to document and to showcase to the western world the modernization of the empire. The Sultans, in particular Sultan Abdul Hamid II, commissioned many of the renowned Armenian photographers to document parts of the Ottoman Empire and to create albums that were presented as gifts to western dignitaries. The Armenian photographers of this generation may not have realized that their images of the empire constituted a genre of photography that we now label as documentary photography. As visual historians, their body of work outside of the studio would set forth a treasure trove documenting the social and cultural history of the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East.